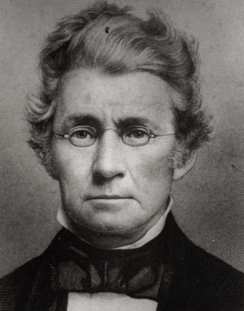

Generations of students have lived in Longstreet–Means Hall without knowing much, if anything, about the Emory presidents for whom the building was named—Augustus Baldwin Longstreet and Alexander Means.

Longstreet had practiced law and achieved fame and fortune as an author before entering the Methodist ministry and then becoming president of Emory (1840–48). Means was a minister and scientist as well as an educator. He served only one year as president (1854–55) because the trustees tired of his trying to juggle his job at Emory while teaching at Augusta Medical College and Atlanta Medical College. Both Means and Longstreet were slave owners and supporters of the Confederacy, but Longstreet was more prominent in defending the Old South.

A native of Augusta, Longstreet attended a private school in South Carolina, where he boarded in the home of John C. Calhoun, the state-rightist and apologist for slavery. Following Calhoun’s example, Longstreet attended Yale, then practiced law back in Augusta, eventually becoming a judge. He also bought the Augusta Chronicle, a newspaper that he renamed the State Rights Sentinel, which advocated political positions in harmony with Calhoun’s anti-Federalist views.

Longstreet’s lasting literary achievement, however, was a series of humorous stories about life in rural Georgia. He gathered some of these into a book, Georgia Scenes, which reviewers at the time universally praised and later critics viewed as a precursor to a genre perfected by Mark Twain. In 2000, Longstreet was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame, largely on the basis of Georgia Scenes.

The book’s financial success provided Longstreet the wherewithal to enjoy a comfortable life. Shortly after its publication in 1835, however, he entered the Methodist ministry. He was serving a church in Augusta in 1839 when the board of trustees of Emory College offered him the college presidency. Longstreet accepted and served until resigning in 1848 to become the president of Centenary College in Louisiana and later president of the University of Mississippi and the University of South Carolina. During the Civil War, he returned to Oxford, Mississippi, where Union soldiers used his personal papers to build a fire and burn down his house.

When Longstreet stepped into the president’s office, Emory College had completed only three terms and was hanging tenuously to existence. A deep recession in 1837 had left the college nearly bankrupt. The trustees no doubt saw in Longstreet a person of intellect, energy, and renown who could lift the college out of its trouble. He traveled throughout the Southeast and as far as New York to garner support for the college. Longstreet also used personal funds to keep the college afloat. On leaving the presidency in 1848, he wrote off the $4,800 the college owed him in loans and back salary—about $149,000 in 2015. All of that totes up on the positive side of the Longstreet ledger.

On the debit side, Longstreet twice became embroiled — and not in a positive way, by our modern lights — in controversy over slavery during his presidency. The first instance grew out of the ownership of slaves by Bishop James O. Andrew, president of the Emory College board of trustees. When the national conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church met in New York City in 1844, abolitionist sentiment in the church prompted a month-long debate about Bishop Andrew’s fitness for office in view of his ownership of slaves. The church divided over the issue. Longstreet was thick in the middle of this debate, firmly on the side of Bishop Andrew and the slave-owning South.

Longstreet also became closely associated with slavery through A Voice from the South, a book he published in 1847 while president of Emory. Framed as ten letters from the state of Georgia to the state of Massachusetts, the volume is an extended argument not in defense of slavery but against the hypocrisy of the North. Longstreet points out that Georgia prohibited slavery until 1750, while New England profited handsomely from the slave trade. Now, with an industrial economy employing what Longstreet calls “white slaves,” the North has had a change of heart about slavery while not changing its heart about “negroes,” whom it excludes from Northern society in various ways. The book is a justification of increasingly popular Southern support for secession.

Remembering Longstreet at Emory, then, requires a balancing of accounts. On one side of the ledger lies his defense of a Southern way of life that we now see as reprehensible. On the other side lies his nearly decade-long work to help the struggling college to survive and, indeed, begin to flourish.

In the next post, more about the building named for Presidents Longstreet and Means.

Gary Hauk

Fascinating, well-written account!

Martin

On Tue, Jan 15, 2019 at 8:07 AM Emory Historian’s Blog wrote:

> emoryhistorian posted: “Generations of students have lived in > Longstreet–Means Hall without knowing much, if anything, about the Emory > presidents for whom the building was named—Augustus Baldwin Longstreet and > Alexander Means. Longstreet had practiced law an” >

LikeLike

Thanks Gary

Always great to read your blog and be reminded of Emory’s long history.

LikeLike

I lived in Longstreet Hall as a freshman in 1968. I always assumed it was named for James Longstreet, the Confederate general.

LikeLike