The evolution of the Emory museum toward its current eminence had no missing links, thanks to the diligence of biologist Woolford B. Baker. When Baker took up the work of part-time director of the museum in 1954, he had already enjoyed more than three decades on the faculty. He would have nearly another three decades in his new role.

One story from the Baker era comes from an Emory alumna, whom I met through email thanks to Elizabeth Hornor, the Ingram Senior Director of Education at the museum. Sheramy Bundrick graduated from Emory College in 1992 with a BA in art history, then stayed to earn MA and PhD degrees and now teaches art history at the University of South Florida. Here’s the story in her own words:

“[In] 1981 . . . I was in sixth grade. My dad took me to the museum to see the mummies after we saw Raiders of the Lost Ark . . . and I became totally obsessed with ancient Egypt. Dr. Baker was there and . . . took us to his office, where he pulled this from a desk drawer and gave it to me as a memento of the visit. I think it’s a safe bet that I wanted to go to Emory because of that day.”

“This” was a square inch of wrapping that Dr. Baker had snipped from one of the mummies. The mummy was, in fact, from the Old Kingdom, the oldest mummy in the Western Hemisphere and one of only six Old Kingdom mummies in museums anywhere. One is in Turin, and the other four are in Egypt. Ours is likely the only one that was a source of souvenirs for school kids.

Finally, here’s where the deer comes into the title of this history, “The Deer and the Pharaoh.” Dr. Baker kept up a steady stream of correspondence with people who thought, with good reason, that the museum would accept nearly anything of interest. For instance, in September 1968, he wrote to a Mrs. Edmund Francis Cook to thank her for her many gifts, including a spittoon, a rolling pin, Korean bridal shoes, Japanese stools, a glove stretcher, a button box with buttons, 29 dolls, and a silver jewelry container “Given to Miss Willie Clover Creagle by Mr. Stephenson of England who built the first dam across the Nile.”

But my favorite of Dr. Baker’s letters is from 1973, to Jeffrey R. Geis of Decatur. Dr. Baker thanks Mr. Geis for the skull of a white tail deer: “I did not have a deer skull but needed one to compare with the goat and the cow which I have on exhibit. If you have any of the leg bones of this deer, I would appreciate them very much.”

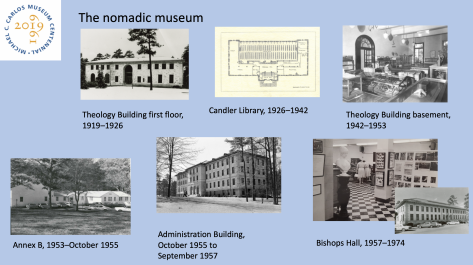

During his tenure, Dr. Baker struggled to raise the museum as a priority for the university. In a history that he compiled with geology professor James Lester in 1974, Baker recounted the nomadic existence of the museum after its move from Oxford, first into the theology building; then into a wing of Candler Library in 1926; then into the basement of the Old Theology Building during World War II; then in 1950 to the wooden Annex B; then, in 1955, into the first floor of the Administration Building; then from 1958 to 1972 into the basement of Bishops Hall—a building which itself is now gone.

Baker’s annual reports to the president tell the story of hope and frustration. After the move into Bishops Hall, the museum mounted its first special exhibition and attracted over three thousand visitors through the year. Seven years later, attendance jumped to 16,355. Emory students made more use of the collections for study, especially the classes of Boone Bowen and Immanuel Ben-Dor, theology faculty members helping to excavate Old Jerusalem. Baker noted that the museum was for many people the first point of contact with the university, and by 1970–71, attendance had risen to nearly 23,000 annually.

Yet the lack of adequate space for storage and exhibitions continued to pose a problem, and the museum now restricted its acquisitions to avoid becoming what Baker called “a cluttered mass.” To make room, the university transferred the Fattig insect collection to the University of Georgia in 1961 and donated duplicate bird skins to the Fernbank Science Center in 1970. Henceforth, the biggest emphasis would be on archaeology and ancient history.

The final report from the Baker years still in the archives, for 1975–76, recommended that the museum be on a par with the university’s libraries and have a central location, with a large exhibition room, space for preparing exhibits, a shop, storage, an auditorium, accessibility, and parking: “A three-story building . . . would be adequate,” says the report. The budget should support a director, an associate director, four curators, a cataloger, clerical staff, a custodian, and programs. It would be a long while before all this materialized.

Next: How a Maytag washing machine led to transformation of the museum.

Gary S. Hauk

Delightful !

On Mon, May 20, 2019 at 8:59 AM Emory Historian’s Blog wrote:

> emoryhistorian posted: “The evolution of the Emory museum toward its > current eminence had no missing links, thanks to the diligence of biologist > Woolford B. Baker. When Baker took up the work of part-time director of the > museum in 1920, he had already enjoyed more than three dec” >

LikeLike