I first posted this two years ago but always like revisiting the story of the first woman to enroll officially at Emory.

As the Emory Law School prepared to celebrate its centennial in 2016-17, a critical question came in from the publisher of the school’s celebratory book—accent or no accent?

The accent in question has inconsistently hovered over the second e in the name of Emory Law’s first female graduate: Eléonore Raoul.

Raoul was also the first woman to be formally enrolled in Emory. Legend has it that Chancellor Warren Candler was away from the campus that day in 1917, when Miss Raoul walked from her mother’s home at 870 Lullwater Road to have a chat with the dean of the new law school in Druid Hills. The chancellor opposed coeducation. Raoul was 29 years old and active in the women’s suffrage movement. She saw no reason why a law degree should not be available to a bright woman who had studied at the University of Chicago. And neither did the dean. By the time the chancellor returned, the ink was dry on Raoul’s enrollment form. She graduated in 1920, the year the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote.

But back to that accent. Raoul was the youngest daughter of the railroad magnate William Greene Raoul, whose work brought him eventually to Atlanta, where he built a magnificent house on Peachtree Street that did not survive the 1980s. Born on Staten Island in 1888, Eléonore descended from French nobility. Raoul de Champmanoir was the original family name.

She grew up among a formidable set of siblings who would go on to careers in manufacturing, farming, charitable enterprises, and political activity. One sister graduated from Vassar and another from the Pratt Institute.

Apparently independent from the start, Eleanore, as she was named at birth, changed the spelling of her name at the age of 24 to Eléonore. At least that’s what I had always thought. But evidence on the web and in publications suggested the possibility that that was wrong. The finding aids for the Rose Library at Emory have it as “Eleonore,” without the accent. But photos available online have captions with different spellings, including “Eleanor” and “Eleanore.”

I had never actually seen her signature. So to the archives I went. The trove of Raoul family papers is large and fascinating. And, happily, I found what I was looking for.

In 1928 Eléonore married a man who had graduated with her in 1920, Harry L. Greene, but she continued to use her maiden name throughout her life in business and professional matters. Here’s an instance of her signature the year after her wedding, on the flyleaf of the financial ledger that covers her checking account for the next two years.

Aha! The accent over the e!

Eleven years later, in 1940, she printed and signed her name with the accent in a document for Trust Company of Georgia.

I go to the library next week to pore over more personal correspondence of this fascinating woman, to whom Emory granted an honorary LL.D. degree in 1979, four years before her death at the age of 94.

Gary Hauk

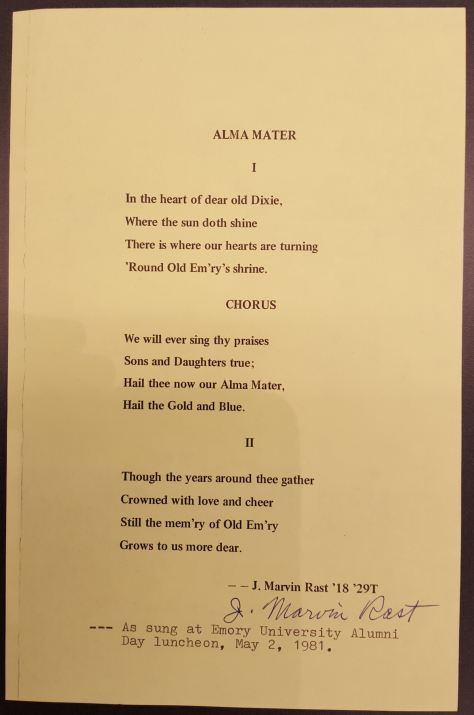

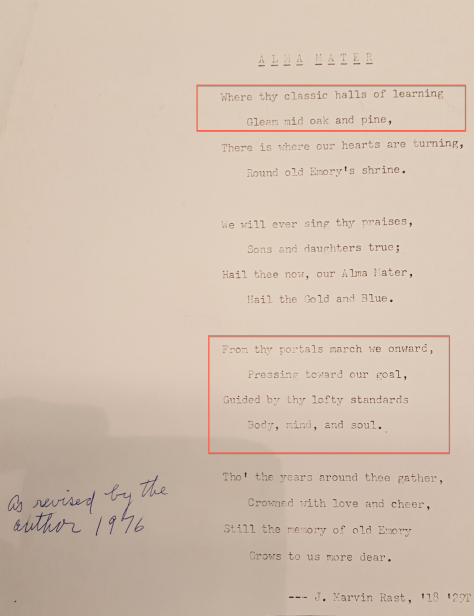

Further correspondence ensued, and by 1981 the suggested changes had made their way to the University Committee on Academic Ceremonies. This august body was chaired by medieval historian George Peddy Cuttino, Oxonian, who, before retiring in 1984, left an indelible stamp on the ceremonies and heraldry of Emory. His committee rejected the proposed changes.

Further correspondence ensued, and by 1981 the suggested changes had made their way to the University Committee on Academic Ceremonies. This august body was chaired by medieval historian George Peddy Cuttino, Oxonian, who, before retiring in 1984, left an indelible stamp on the ceremonies and heraldry of Emory. His committee rejected the proposed changes.